-

Death: A Shift In Perspective

This was the second assignment for my mythology course, uploaded now for a sense of completion.

Fractal Hassan

Mythology | HUM – 2310

10/16/2022

It is often asked amongst philosophers what topic in philosophy has plagued philosophers more than any other topic. Perhaps the most striking of these questions is asking ourselves what it means to be human. Many people have tried to answer this question. Linguists like Noam Chomsky would argue that language is what makes us human, until it was discovered that many other animal species have rudimentary forms of language-like communication. Some culinary artists would argue that no other species possesses the ability to cook—and so far, we have not found chefs amongst the animal world. What some anthropologists, including mythologists such as Joseph Campbell, would argue, is that humans possess a unique awareness of their own lives and their own mortality—enough so that they start to contemplate about the meaning of such a life, the meaning of their deaths, and what may lie beyond that seemingly final barrier.Humans are then the creatures who notice that the shadows on the walls of the Cave may not be true representations of these figures, and dare to try and venture outwards to find the mouth of the Cave to try and catch a glimpse of the true forms. These people explore the Cave, explore outwards, and then return with stories of that which they saw, i.e. the mythologies that aim to explain the True Nature of Things. Different cultures went through these processes in different ways, and perhaps we will never know the true origin or motivation of the first people who dared to venture out of the Caves, but we do know that the very earliest signs of mythological thinking involve burial rituals [1.32, 2.10:02] whereby people (and indeed animals) were buried not without intent, but with a certain method and carefulness, perhaps with fetish items or otherwise grave gear. Death, then—the fear of, or in some way, the fascination with it—was the earliest driver of mythological thinking that drove humankind to have a sort of mythological instinct that drives us to storytell; perhaps we see the storytelling instinct even amongst the secular types in the form of the adoration of fiction and heroic stories of the cinema, and the grandiosity and appellation adorned upon historical figures deemed to be Heroes. It is impossible to escape the grasp that mythological thinking has on the human psyche, and understanding precisely how it entangles all of us into one greater tale will help us understand our own psyche and our own role in the greater tale of humanity’s mythology.

In many cultures, the ideas of life and death are intertwined as part of the same story; in Genesis [3.57], for example, Eve becomes both the Mother of all life, as well as the scapegoat for suffering and death. The Serpent then, being another symbol of the Feminine (as the shedding of its skin is akin to the cycles of menstruation), connects the sin of obtaining the knowledge of good and evil (and the awareness of death) to the Feminine (more specifically, the womb). This then alludes to an eternal cycle, tying back the end, being death, with the beginning, being Life, through the Lifebearer, being the Woman.

In some other cultures, the reason for death is considered a separate matter from that of life. There is no such “sacred land” which a Navajo spirit would continue onto, as in Navajo mythology, this world is considered to be the sacred land and the most desirable one [3.98]. Many cultures have ceremonies surrounding the primary animal they hunted for food and clothing; while the Ainu people would treat bears as sacred [1.32] and have rituals honoring them, many Native cultures would have similar rituals for other food animals, such as the Blackfoot tribe with Buffalo [1.35], or salmon with the Navajo [2.14:35]. Indeed, it does seem like there is this commonality of atonement related to the death of the food animal amongst many cultures, at least when it comes to animals. This is something that the Abrahamic religions only emphasized as it transitioned into Islamic mythology (as can be seen with the necessity of halal meat in the belief, although it existed as far back into the Jewish era what with kosher meats), although atonement for animal sacrifices were largely not heavily emphasized in the earliest renditions of Abrahamic mythology.

It’s interesting to note that while Abrahamic religions greatly emphasize human death while hardly touching on animal sacrifice, Navajo mythology is quite the opposite. While the Navajo culture has many intricate burial or sacrificial rituals surrounding the death of animals, the death of a human is far less emphasized, although death rituals do exist [5]. There is a great fear of the dead, and burials are often done carefully and with intention as to, so to speak, prevent hauntings [4]. There is no “sacred land” that exists beyond this world. This world, as a result of the actions of the Air People in its creation mythology, is the “sacred land.” Thus, while there is no belief of reincarnation nor transcendence in Navajo mythology, there is no absolute death, and the spirits of the Navajo walk this world freely. There is an interesting stark contrast to see here, between the Abrahamic writings and the Navajo storytellings: the way which death and in particular this life is framed is starkly different.

Perhaps one of the most common archetypes one can see analyzing the mythologies of this world is this idea that there existed better times that have fallen to what is currently seen as “hard times.” With Greek mythologies, there is an allusion to the five ages. There exist hints of this in Vedic traditions, as well as Germanic traditions [3.45]. In the myth of Genesis, this era of a “Golden Age” was the era of Eden, i.e. that time which Adam and Eve lived peacefully in the Garden, prior to consuming the fruit that would give them the knowledge of Differences. Perhaps it is quite interesting, then, to see the Navajo myth greatly diverge from this general archetype of “fall from a better era” as its mythology greatly focuses on an emergence from a worse one, i.e. we are living in the Golden Era [3.98]. This then alerts one to an interesting observation—precisely that world view in which the Navajo viewed this world not as a place of suffering, but as a blessing to enjoy, and the world around them as deeply sacred and as a gift to humans from the Gods [3.111]. Genesis, in contrast, stresses that humans exist in this realm, in this plane, as punishment for Eve’s “wrongdoings.” Thus, whereas the Navajo myths highlight the beauty in this realm, the myths of Genesis and Abrahamic teachings highlight its horrors.

This condemnation of differences can further be contrasted, as Navajo mythologies highlight differences from the start, being chock full of Quaternities. There is a strong emphasis on the differences of the cardinal directions [3.106], as well as strong color symbolism throughout its mythologies, emphasizing the different colors that are adorned on the creatures (such as an aetiological explanation for grasshopper colors [3.109]) and realms within it. These differences being spoken repetitively throughout the myths would suggest a deep importance to differences existing, which is strongly contrasted to that of Genesis, where the very concept of “being different” is deemed to be forbidden knowledge by God’s decree, and is the foundation for its entire mythology. This can further highlight an emphasis on life, rather than death in Navajo mythology, as contrasted with the Abrahamic beliefs. It does not require much thought or research to ascertain this world which we live in now is incredibly diverse, filled with countless differences, and filled with variations beyond what is conceivable and comprehensible. It is rational to understand why the culture which celebrates differences would see this world as being more desirable than the one whose entire mythology is structured around this unwanted unveiling of said differences (i.e. the condemnation of being different). That there could help one understand why the Navajo beliefs puts far more emphasis on how to live (i.e. a principal guide for navigating this life without regards to post mortem philosophy), rather than the Abrahamic emphasis on “how to die” (i.e. one does these rituals in preparation for death when they meet their maker), as this world is already the desired one.

Perhaps it is no secret as to why Native cultures such as the Navajo people consider the entirety of nature to be sacred, and the act of the White Man coming and pillaging nature and slaughtering their sacred buffalo to be an act of vile and vehement desecration. Their mythology, their creation story, was not created out of a fear of death, but a reverence for life itself—all of life, all of nature, everyone and everything in it, being all part of a grand dance in the ballroom of this planet, dancing to a billion year old tune that harmonizes all of us as a part of its song. Life, to the Navajo, is in and of itself a sacred thing, and we exist because of, not in spite of, sacred gifts. While Genesis alludes to this world being the worse off one due to the awareness of differences, the Navajo see these differences as a thing to be revered and loved, as differences are a part of nature and a feature to be adored. By analyzing their respective mythologies, one can see a relative trend that generally points to the Abrahamic myths teaching one’s life preparing one for death, and the Navajo myths teaching one’s life being focused on this world and the life in and around it despite of death.

Hereby we can see two sides of the coin—how does one rationalize and cope with the insurmountable wall of death? This philosophical question, that permeates all of mythology on some level or another, this philosophical question that is a fundamental driver for all of mythology. One can live their life preparing themselves for what may come after it, or one may use it to gain incredible perspective of what life exists around them. The Navajo people do not focus on death, it does not focus on an afterlife or what may lie beyond, nor does it focus on what one must do before they die. The Navajo mythology aims to help people navigate and appreciate this life, especially with regards to nature and the people around one’s self, whereas Genesis asserts we exist here in this life due to Original Sin (Eve consuming the fruit, obtaining the knowledge of Differences), and we must atone ourselves of this sin in preparation for death, in order to rejoin God’s kingdom. The view of this world, the view of death, between Genesis and the Navajo myths are almost inverted, and thus show a very stark contrast on how human mortality is viewed. The Abrahamic viewpoint tells one to live for death; the Navajo viewpoint tells one to live for life. Both are guides for living one’s life despite one’s mortality; only the frame of reference shifts from one of pessimism to one of optimism.

Perhaps this does highlight an interesting facet of the human psyche and how one comes to terms with one’s own mortality. Whatever belief system one chooses to believe, regardless of origin of spirituality or religion, one will always be confronted with that seemingly impenetrable wall of death, and how one should structure their life knowing they will one day succumb to that wave. Some may structure their lives in preparation for whatever they believe lays beyond it. Some may structure their lives so they make most of what the sacred act of Being Alive has to offer. Whatever it may be, whatever belief one may have, everyone everywhere will die one day, and we must all make decisions knowing that fact. Making these decisions, with death as perspective, is what the very first Paleolithic humans did 200,000 years ago, making the choices to develop themselves and their community that would cascade into the society we see today. And perhaps it helps to think mythologically; as Joseph Campbell points out, the lack of mythology in today’s society is in his opinion part of the reason for its decline [2.39:18]. Fundamentally it all boils down to one decision: will one choose to live life in preparation for death, or will one live life with all this life has to offer? These are not mutually exclusive quests, and one may find wisdom in attempting to achieve both. The real takeaway then, is that death is the grand unifier of all things in this universe—all things live and all things die; some things just live far longer than us. But how we, how humans perceive death, and how humans shape their lives around this awareness of death, is something, as far as we know, intrinsic solely to us. This journey from the womb to the grave is a meandering stroll that one takes; the path one takes and what one collects in this journey to plan for the next one is a deeply personal decision one must make along this journey. And what matters not is what the journey entailed; it is the satisfaction one has with where they went and what they collected before laying down at the destination that is what determines how meaningful and important that journey was.

Bibliography

- Campbell, Joseph. Myths to Live By. Penguin Compass, 1972.

- kinolorber. “Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth | Ep. 3: ‘The First Storytellers.’” YouTube, 23 Aug. 2022, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ij5cJtYLkvE.

- Thury, Eva, and Margaret Devinney. Introduction to Mythology: Contemporary Approaches to Classical and World Myths. Oxford UP, 2022.

- Navajo Culture. navajopeople.org/navajo-culture.htm. Accessed 16 Oct. 2022.

- Navajo Death Rituals | Navajo Code Talkers. navajocodetalkers.org/navajo-death-rituals. Accessed 16 Oct. 2022.

-

What Is Myth?

In the mythology class, I had written four essays. The Stanley Parable one I wrote was the third one, uploaded as I wrote it. The Rite of Passage one I uploaded late. The two others were this one, the first assignment, and another one I’ll upload alongside this, the creation myth assignment.

Throughout history, mythology has been a vehicle for the human imagination. One cannot say for sure the spiritual significance of these stories and whether or not these Gods and Heroes do exist on some other plane or dimension, but one thing is known for certain—the stories of which these Gods and Heroes acted through had a very real influence on civilization, and can help provide us with a deeper understanding of the human psyche as well as a glimpse into the past through the lens of those who experienced it, and the descendants of those who told the stories.

Joseph Campbell paraphrases Jung when he frames myth as a dialectic between the conscious and unconscious mind [1.15]. Myth is therefore a form of window into the depths of not just one’s individual consciousness, but an apparent collective consciousness that drives much of humanity to reinvent or perpetuate certain themes that exist across numerous cultures throughout the world. While these unconscious archetypes and drivers are not yet fully understood (although Campbell suggests that some of the earliest conceptualizations of divinity date back to the Neanderthals, who potentially may have worshipped fire as a form of deity [1.36]) their expressions and effects are echoed through the stories and myths told throughout the world [1.21].

Myths can serve many functions, but mythologists assert that myth is an alternative method of reframing one’s conceptualization of existence from a narrative perspective with what best scientific knowledge exists at the time [2.9]. It allows one to better understand and predict how one’s external circumstances will behave and react, albeit not by scientific means. Long before chaos theory and fractal geometry were ever conceptualized, cultural groups formed mythologies to attempt to explain the chaotic behavior of nature, so that one may better be able to understand how these resources are distributed to more strategically plan their methods of harvesting the resources [2.9]. This would be an example of aetiologic mythology, i.e. an attempt to explain some external natural force through supernatural, metaphysical, or by other mythological means.

Perhaps one of the most striking and fascinating features of mythology is this interplay between facets of lived reality and the metaphysical, whereby mythological events often include real stories, perhaps as a method of ontologically justifying certain events that have occurred (for example, the siege of Troy being the result of a jealous contest of attractiveness amongst goddesses [2.10]). Throughout much of mythology, we see these themes echoed through history, of fact and (at least, literally, but perhaps not necessarily metaphysically, false) fiction intermingling as a form of storytelling and bookkeeping, so that one may continue to hear the tales of the great very real heroes that permeated many cultures.

One such story that has reached much popularity and has been retold countless times in many countless forms is the tale of Jason and the Argonauts, which has at least one modern movie as well as the Percy Jackson retelling of the tale. When one visits Greece, while one will seldom meet a Greek Pagan who truly believes in Poseidon and all the gods involved in the tale, even the most Orthodox of Greeks will exude an air of mysticism and reverence for these tales that built their culture, that formed their country, that brought forth what makes them, them. One merely needs to stand in the middle of Athens, under the Parthenon, to realize these myths are still very much alive and breathing in the culture, deeply ingrained into the Greek way of life, into Greek ritual and beliefs. During Easter, one will still find Greeks sacrificing rams [4], perhaps not to Jesus or the Abrahamic deity, but as an echo of their past, where sacrificial rams were used to celebrate the seize of the Golden Fleece, up until the early 20th century [3]. This can be seen as a form of an anthropological insight [2.14] from mythology; despite these myths perhaps being a Pagan whisper in the wind these days, the cultural influence weighted from these myths have shifted a culture so drastically that it is deeply rooted in their collective unconscious, as a fundamental driver that they feel drawn to expressing as a form of cultural identity. Perhaps the days of human sacrifice are (hopefully) over, but the small details of cultural tradition live on in the smiling hearts of the Greek people, who while largely perhaps see and know these myths to be literally false, see them as cultural truths that built who they are today.

In certain parts of modern-day Turkey, where these myths extend to, these myths are heralded as sociological truth. One version of the myth heralded that Jason’s ship, the Argo, sank on a small island the locals call Cape Jason [3]. Their fork details how Jason was a real person, whose crew settled on the island and married the local girls, whose descendants are believed to still live on the island to this day. Perhaps this could never be truly verified; after all, we do not have Jason’s DNA sample to test the population against; but regardless, the belief of this direct lineage creates a sort of “belonging” to some special group of people (i.e. those descendants of Jason and his crew) that surrounds their particular version of the myth, and it is a driver for the culture that thrives in that area.

While it is perhaps not quite literally true that a hero snatched glimmering wool from behind the snarling maw of a great and fearsome dragon, these tales of heroism built a culture several thousand years old, and its influence was so great that entire regions of the world still find value in them and celebrate them, despite having shifted away from the core driving beliefs that shaped the initial myths. Myth then, cannot simply be framed as a mere fairy-tale, nor can it be seen as a story made by the scientifically uneducated; it must be seen as a heavy interplay between history, anthropology, metaphysics, and imagination, all woven together by clever storytellers whose goal was to entertain and educate in the most memorable manner possible, in a way the culture at the time could largely relate to. It cannot be simply seen as a relic of the past, as its influences have trickled down and worked its way into every culture in every latitude and longitude of the world, consciously or unconsciously, in a form of cultural and artistic expression. Myth then is a form of self-expression, and truly a way for humanity to understand itself, where it came from, and where it’s going. Myth will not die, as much as Sir James G. Frazer wants it to; myth is us, myth is humanity, and myth will follow us for as long as there exists life to think about itself, and what it means to be alive.

1 Campbell, Joseph. Myths to Live By. 1972.

2 Thury, Eva M, and Margaret K Devinney. Introduction to Mythology. 4th ed., Oxford University Press.

3 Wood, Michael, director. In Search of Myths and Heroes. Jason and the Golden Fleece, PBS, 13 Dec. 2011, https://fod-infobase-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/p_ViewVideo.aspx?xtid=44322&tScript=0#. Accessed 25 Sept. 2022.

4 This was actually a personal experience from when I visited Greece in 2009 or so. I do not know how I am supposed to cite this.

-

Transition: A Rite of Passage

[Essay Written 12/09/22 for Mythology Class]

Many a lot of philosophers and anthropologists try and pinpoint the pivot of history where we stopped simply being homo sapiens and became what we know today to be humans. It is known that no known animal truly has a concept of death beyond “ceasing of being” let alone what lies beyond death. But we as humans have something truly unobserved in nature—that ritual which surrounds death. The ritual of death is one of the earliest known forms of ritualism [1.32], and the presence of ritual in human culture has only permeated our culture and rooted itself deeper into the collective unconscious. Fundamentally the principle of ritual defines a transition or transmutation of one state of being into another, be it something so arcane as expanding one’s consciousness by communing with the devil on the full moon, or as mundane as that which everyone experiences, like death.

Perhaps less “ritualized” in western culture but no less universal is that ritual ascribed to the process of puberty. Puberty is an inevitable stage of growing up, representing this transitionary period of childhood to adulthood. In many non-Western cultures, puberty is marked by a social set of predefined actions and activities that serve to symbolically mark this transition from childhood to adulthood. These rituals, these actions, these principles that serve to drive this rite of passage, are part of a system of “stereotypes” that Victor Turner defines to give structure to this or any form of ritual [2.6:57]. By “stereotype” one does not imply the negative connotation of such, but instead the positive connotation that denotes an underlying behavior that seeks to drive a certain result forward within the context of a particular culture.

Humans are not inherently “stereotyped” beings—such is an old, outdated, and scientifically inaccurate idea—unlike animals such as the bee who is stereotyped inherently to create such perfect geometry in the hexagonal structure of its home. Joseph Campbell would suggest that humans are instead “open” creatures [1.45] that are then formed and imprinted on by the society they grew up in. Campbell would suggest that we are, as children, imprinted upon by the adults we grow up around, thereby being “stereotyped” as to how adults are and how they as adolescents should act, through this switching from a system of dependency to responsibility [1.46].

Freud would suggest that the function of ritual is much different in the Western culture [1.47], stating that we as members of society are responsible for our own “reality function” i.e. the awareness of the social programming that surrounds us and our capacity to form our own sense of becoming and being despite this presence of social programming. This would contrast starkly with cultures where the members of it are in fact stereotyped through the process of ritual and coming of age as to form their identity within the context of that society, rather than the more Western form of individualistic becoming.

While Joseph Campbell suggested that form, structure, and ritual is what gives society its glue and structure [1.52], one must understand the era of which he has written this essay in—i.e. before the age of the computer, before the age of the internet, before the age of hyperconnectivity and information flow that allows individuals to form their own sense of communitas within an aggregate of individuals that form a collectivized set of experiences through individual adventures of soul searching and identity formation. Perhaps one of the strongest senses of modern communitas formed through the intentional subversion of these identity rituals and adherence to form and structure is such community found throughout LGBT groups. While the expressions and identities found within the non-cis and non-hetero subgroups within the LGBT umbrella are practically infinite, perhaps no community subverts the rite of passage more than the transgender community.

Joseph Campbell suggests that rituals generally have an underlying form of mythology that forms the greater infrastructure of a set of rites and rituals [1.57]. Perhaps while it is less seen in Western culture, one can look to other cultures, such as Indian cultures, to see evidence of a mythological superstructure driving some of the earliest examples of transgender expressions. In Indian culture, transgender individuals are called hijra, a term traditionally used to refer to male-to-female individuals but can be used to describe any trans person in general, and the hijra were considered sacred embodiments of Shiva—a deity that embodies both the masculine and the feminine form. Shiva could shift between a male and female form, similar to how a hijra would have both the masculine and feminine aspect within them (although such may be a point of argument amongst modern transgender individuals, many of whom want no connection to their birth gender), which thereby led to a general belief that these hijra were mythical beings—i.e. trans people were considered as mythical beings, or otherwise beings with mythic qualities. Similarly in Native American cultures, genders and even names are not final until the individual goes through their own process of mythical self-discovery, often through a ritualistic and mythical process, that defines who they are not at birth but at a later point of becoming in their life.

In Western cultures, gender is less defined by culture and mythology, and is seen as a performative act [2.18:29], much in the same sense of Shakespeare’s idea that “all the world’s a stage.” We as members of society play a certain role—in this case, the role of Man, that takes the role of the tarot Emperor archetype, and the role of the Woman, that takes the role of the tarot Empress archetype. While Jungian archetype theory would suggest that we all have both the Emperor and the Empress within ourselves (he himself lamenting on how he neglected to explore his feminine side), such expressions are repressed in this Western society where people are seemingly assigned preset social roles, functions, and expectations based on the set of genitals they were born with—if one is born with phallic genitals, they are deemed to be the Emperor, and to express the Empress is a sign of weakness; if one is born with yonic genitals, they are deemed to be the Empress, and to express the Emperor is crossing a line of predetermined power. Where these certain power structures and assignments have come from is unsure—but what is sure is that such assignments are not static, as these dimensions of what the role of Man and Woman must do has constantly changed. This in and of itself shows the performative role of gender—i.e. that role one is assigned at birth based on the expectations this greater roleplaying game of society has for them. The realization of this performative role—and the desire to perform the role not what was assigned to them, but what one designs for themselves, then is a major driver as to the rise in experimentation of self-expression as is seen in modern society.

Modern society is used, as opposed to “Western” society, as the impact that technology and the rise in ease of communication that has occurred over the last 50 or so years, and with the advent of technology that makes information to access easier than ever before, has led to more people around the world, not just in the West, aware of their performative role in society, the existence of transgender individuals not just in the west but within the scope of their own culture helping more individuals around the world become more sure of not just who they are, but who they themselves want to be, not simply what society wants them to be. For example, a good portion of the information sourced in this essay was sourced through the (as of writing this) newly released AI chatbot, ChatGPT [3]. One may simply query it as they would a human being, and one will get a coherent response that strives to be as academically correct and unbiased as possible. Further examples of such are gender-swapping Ais that aim to show one what they would look like as an inverted gender, which has been a major player in helping “eggs” (people who have not yet realized their transgender identity) figure out their identity. The rise in information technology, and the rise in widespread deployment and access to AI has led this experience of transgender expression to be found not just in Western societies where ritual has less importance, but in many ritualistic societies around the world, like in India. It is hard to say whether globalistic use of technology will over time diminish the ritual and Rite of Passage, but it should be noted that while the act of transitioning is not a ritual or rite of passage in the traditional sense, it still holds many traits and forms of a traditional ritual, although in a transformative form.

Victor Turner defines a ritual by three stages or dimensions: the exegetic, operational, and positional stages. The exegetic dimension expresses the internal structure of a ritual i.e. that who practices the ritual. This here, then, is the trans person themselves, as a “player character” in this ritual where one is embodying a role that better suits them they are becoming into. [2.9:35]. On some level, it also represents the symbolic meaning and significance to the ritual—something deeply personal and unique to every trans person who undergoes their transition [3]. This could also represent the process of self-discovery and self-expression the trans person undergoes through their process of transitioning. The operational stage are those on the fringe of the ritual, the officiator or thereby a bystander that witnesses those undergoing the ritual—in this case, the allies one has that forms their support network i.e. their sense of communitas as they undergo the transitionary process form the operational dimension, alongside the external actions the trans person may take to fulfil their transition, such as hormone therapy, getting a haircut, getting new clothes. The positional role, then, is a combination of both of these—being the fulfilment of identity through a legal name change and legal gender change, as well as such’s functional role in an external society. From an informational perspective, a cis person reading about a trans person’s experience or thereby how their transformative role fits into society, would also be taking a positional role, as they have not truly experienced what it is like to be a trans person—one is alien to dysphoria, the lack of self-identity in gender expression, and that feeling of wanting to become something else. In some ways, ChatGPT, which was used to augment many of the ideas in this essay, so too takes a positional role, as it merely looks at the sum total of all knowledge about trans people and the transgender experience—it itself never did the research, nor does it know what it is like to be trans, thereby its information is positional.

There are two described types of ritual: the liminal and the liminoid. The liminal rituals describe this straddling between two forms of existence within society [4.510] i.e., the main differentiator between one’s pre-ritual self and their post-ritual self. The liminoid, then, was developed as an alternative within a more pluralistic society like in Western cultures, to represent the more “playful” or “creative” aspect of a ritual. In this sense, the process of transitioning is both liminal and liminoid [3]. The liminal aspect of transitioning is represented by the stark contrast of a person pre-transition and post-transition. Not just this person visually and grammatically changing, so too is their internal world changing, as they transition from someone unsure of who they are into someone thoroughly confident in their identity. There is also the very formal aspect of the legal officiators of the change—the name and gender changes—which mark an officially recognized aggregation into society. The liminoid aspect, then alludes to the individual trans experience where they “play” with their identity and figure out who they are—it is a necessary stage in the self-discovery process to play with one’s identity in order for them to find out what is right for them.

The transgender experience then is a subversion of the rite of passage; while not relying on traditional rituals and rules and in fact attempting to break tradition, one still goes through the three stages of the rite of passage. [2.31:00] The separation phase would be that point one realizes, and accepts that they are trans. They perhaps choose a new name for themselves and a set of pronouns that better fits them. This is a literal “separation” from their past identity, and starts their journey of becoming into their true self [3]. The “transitionary” phase is what trans people themselves refer to as a literal transition—that which they introduce their new identity to trusted individuals, as they play with their identity amongst people they deem safe, through the interplay of the liminal and liminoid nature of the experience. They may buy new clothing, change their hairstyle, and attempt voice training, perhaps also starting hormone therapy, or getting surgery to better fit their ideal body. This is where the individual would find and build their communitas, and their sense of identity within the larger LGBT and allyship communitas in a society that otherwise ostracizes such individuals. The reincorporation, or aggregation stage, would then be that official name and gender change, and the outward social transition outside of the formed communitas that attempts to finalize their last stages of transition in society.

Much like a puberty ritual is not a finality for adulthood—and adulthood and self-identity is a constant state of flux and becoming, the process of transitioning never truly stops. In that sense, transitioning is a cyclical ritual, one where people discover new aspects of themselves, pursue a miniature rite of passage into becoming that new self, and emerging on the other side within their communitas as a fresher, updated version of the self. It is to note that this process is not unique to trans people and is a feature of all humans—we are not static beings with static personalities, with static likes and dislikes—much like Heraclitus said before, change is the only constant—and we must all recognize the change within us and become the self we want to be, not simply being what society asks us to be.

In some sense, unfortunately, trans people never stop being the “structurally dead” neophytes Victor Turner mentions [4.508]; upon giving up their previous status of being cisgender, one will find themselves permanently ostracized in a society that is yet to normalize transgender individuals; such comes the importance of the communitas built through the transitionary process as this allows the trans person to be able to aggregate back into society—a society that accepts them and sees them as the newly emerged person that underwent the rite of passage into becoming the person they were meant to be—and supporting them in their journey forward as they and all within that communitas constantly figure out who they are.

It is to be noted that the existence of transgender people have existed in cultures far older than western civilization, and it is not a product of “western decline” as some may call it. In a culture devoid of rituals, one struggles to find their identity and must make do to explore who they truly are—in this process, they may discover they are not the gender assigned to them at birth, and then follow the pursuit of undergoing their own, created form of rite of passage, one taken not because society asked them to, but because society asked them to be something they are not, and they are trying to break free of it. Rite of passage itself is all about transitions, and the act of changing one’s self as a trans person itself is called transitioning. Even the very laws of physics necessitates change, and as stated before, change is the only constant. We are all in a state of transition, from one state of being into another state of being; the transgender experience merely seeks to take control of becoming and directing it to manifest who one wants to be, not where they’re pushed to be. We must all recognize this constant transitionary state in our lives, that we are all living in a constant cycle of becoming and coming into, and a firm understanding of who we are and where we want to go is what it will take us to the fullest version of and ideal of ourselves. The rite of passage marks specific points in our lives that are particularly notable, but in reality, every experience we learn from is a rite of passage, as we emerge from it fundamentally changed from who we were before. If we don’t take everything for granted, and take each moment, no matter how humbling or simple it may be, as a learning moment, and strive for a constant state of becoming, one embraces the change, the constant state of transition, and one may find themselves farther than they ever thought was possible. May change drive us all forward, and may we emerge from each experience better learned, more knowledgeable, and far wiser than we were before.

References

- Campbell, Joseph. Myths to Live By. Penguin/Arkana, 1993.

- Warren, Bob. “Ritual Presentation.” YouTube, YouTube, 18 Jan. 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y0DTPq37HOA.

- ChatGPT, OpenAI. https://chat.openai.com/chat. 12/09/22. Discussion by Fractal Hassan. Full transcript available upon request.

- Thury, Eva M, and Margaret K Devinney. Introduction To Mythology: Contemporary Approaches to Classical and World Myths. 4th ed., Oxford University Press.

-

Not Left, Not Right, But (Digitized) Love

In this day and age of consumerism, it is so easy to buy into parroted beliefs slung by the left and right, of “there is no ethical consumption under capitalism” or that “poor people need to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps.” With tensions rising and mounting between those on the left and right–as the left adopts an anti-work mentality whereas the right installs anti-homeless architecture, we start to see why there is growing tension between the members of the economic left and the economic right. While there is some things to be stated about the other aspects of these political ideologies–be it forgiving dictators of countries one didn’t belong to, or outright animosity towards entire classes of people who simply exist and cannot control their existence, I here aim to primarily focus on this idea the left and right seem to adopt of “capitalism bad, communism good” or vice versa that is so prevalent amongst the members of our society is an intrinsically outdated ideology in a day of virtually infinite, free information in ways the forefathers of these ideas couldn’t have even begun to consider as a potential reality, leaving room to entirely rehash what “left” and “right” even mean in our day of eternal connectivity and endless information.

It is worth noting that Adam Smith himself stated “A man must always live by his work, and his wages must be at least sufficient to maintain him,” in the very book that defined the modern definition of capitalism, The Wealth of Nations. It was stated by the father of capitalism himself, that capitalism inherently requires a living wage and a healthy workforce (although Smith did not directly comment on the idea of “minimum wage”) to even function, while Marx goes on to critique from within Das Capital that the accretion of wealth unchecked will lead to irreversible inflation that could undermine the foundation of the entire capitalistic model. Adam Smith further does support the idea of unions, so long as the interests are mutual with the capital, and not in mutiny of the capital. Therein lies an “us vs them” mentality from both sides of the dialectic, of capital vs labor. Now Marx goes on to further dismantle capitalism in Das Capital, but Marx failed to realize what was to come just a century after his works were published, with the burgeoning boom of technology creating a form of interconnectedness and near limitless access to information that was the stuff of fantasies just decades prior to today.

In the day and age of information, what with search engines like Google and Bing being veritable Libraries of Alexandria that offer the sum total of human knowledge at literally anyone’s fingertips for free (even if one does not own a device, largely having access to one’s own public library allows one to learn just about anything for free.) With Google transforming into a powerhouse as a cloud a mere decade or so after its inception, and Microsoft following suit with a search engine model, the rise in free tutorials all over the web was unprecedented, particularly on platforms like YouTube, by both independent YouTubers (I myself only learned to code with the utterly precious Bob Ross of programming known as Daniel Schiffman) and entire degree audits published by major universities such as MIT (with MIT OCW) and Stanford (Coursera) publishing free or next to free oceans of information available to just about anyone with the push of a button. What with K-12 free learning platforms like Khan Academy existing as well, and what with major tech companies such as Google, Microsoft, and Amazon highly pushing certifications and GitHub projects over one’s college degree (this article of data comes from an insider I know, although you better be damn good if you don’t have a degree or at least have a partial degree to compensate–but your luck is pretty decent if you are an existing Computer Science or Information Technology track student with your cert and GitHub route), well-paying jobs are becoming more and more accessible to just about anyone with an internet access.

With the recession looming and daring to push us into the Great Depression: Electric Boogaloo, several companies all across the board are causing massive layoffs that strike fear into people’s eyes about the depths of the recession and how they are going to manage to live within the confines of this recession. We must ask ourselves an essential question: If it is effectively, and essentially entirely free to audit an entire lifetime’s worth of education for virtually free or next to free, and with the cost of most lifechanging certifications not more than forgoing two week’s of Starbucks, why aren’t more people spending time to educate themselves? Part of it may be doomer mentality–and this idea that we see most commonly amongst Millennials and Gen Z, that we are all effectively on a sinking ship–the ones that think everything is fine are on the nose end of the Titanic hoisted high in the air ignorant of the drowning ship pulling everyone down. Now while this seems to currently be the case regardless of who is in charge–as unregulated anything, be it capitalism, communism, or Pastafarianism, can lead to disaster, as there isn’t any one answer in any one solution that wouldn’t lead to the ballasts of our ship being too biased in one direction or another.

This is why we must abandon this old idea of “left” versus “right” and accept that there is virtue in both ideas, and that adopting a framework of “communism for one’s Maslow needs, and regulated and checked capitalism outside of that” will allow for one’s very basic, very primal needs to be taken care of–i.e. those needs that are required for one’s basic stasis. One might bring up UBI, but UBI is a poor solution, as most people are poor mitigators of their own finances. Instead of UBI, an accreditation system that allows one to have very basic shelter, nutritional food and clean water, and (in this modern day and age) basic access to the internet (even with administration limits set to limit social media hours and to encourage access to educational materials), as well as basic guaranteed access to a Primary Care Physician (PCP), as well as the reduction of drug stigmatization and availability of recovery programs, to help streamline struggling people towards having the boots to pull the straps of in the first place. One cannot pull straps if they do not have boots, and it is up to us having basic compassion towards others to ensure they have the boots to strap themselves up to help them move forwards.

By providing nonmonetary support towards these people in the form of social assistance and social programs, and providing resources for these people to educate themselves and find jobs for them to move outwards and forwards. Even Marx himself stated, “Those who are able to work, but refuse to do so, should not expect society’s support,” of which I have noticed many anti-work leftists conveniently ignore. At the same token, the right conveniently ignores Adam Smith’s insistence on the importance of unions and a living wage and treating your workers fairly (as I have provided resources to earlier). Marx’s theory assumes a post-scarcity society, whereas Adam Smith implores the importance of capitalistic supply and demand metrics in a society reliant on scarcity. Now while on a material level we do exist in a scarce society (although we have more than enough resources to feed and house all humans, should we adopt a less wasteful mindset–the specific source of this stat will be in the lighthearted embedded video at the end of this article), we also live in a day and age that neither Adam Smith nor Marx could’ve ever envisioned, in an era where information and data is not only post-scarcity, it is dangerously post-scarcity. We have so much information, that we are rapidly running out of places to put them, and the data centers that are hosting them, that have not switched over to renewable resources (of which themselves are blamed for nitrogen emissions), are starting to use almost 2% of our entire energy infrastructure (don’t make me dig for this stat it was buried in the mountains of cloud resources I have read over the last few weeks–but this is a very, very modern an up to date stat–I think the number is more accurately 1.8% if I remember correctly don’t make me GTFY–Google That For You, because seriously if you don’t know how to fact check and Google things in 2023 this is probably not the right article for you to be reading anyway).

Our hunger for information and data is both a blessing and a curse; for one, those that lament the loss of the Library of Alexandria fail to see how they essentially have its modern equivalent in their pocket–with the added promise of an essentially free real-world parallel of the Akashic Records being built of them in the physical realms (I could write an entire other essay on my opinions on data privacy and how we as a society living in an AI-driven, data-driven era must adapt new and modern frameworks on how we treat ourselves and our data within this new and burgeoning era of data-driven technology)–and use their search engines merely as a hotlink to their favorite social media, or maybe reading what the hottest news about the latest celebrity is. As someone who has spent his entire life on the likes of Google, YouTube, and other free online learning platforms (and developing one of my own!) it… frankly disgusts me how people are so myopic with how they don’t see and treat these technologies as potential, effectively endless, free learning platforms that could easily put a zero or two in their salary for free if they simply set aside a few hours a day to learn something new (and knowing not just what but how to Google things in and of itself is a skill one must learn, as most people don’t realize that “site:.edu” is an easy way to filter sites to reliable sources, or that simply putting things in “quotation marks” forces verbatim results).On one hand, yes, we must address the socioeconomic problems that we are facing in this world, regarding the rampant unemployment rates (actually if you just Google “unemployment rate” they have a really nice built in live metric system with lots of nice statistics–which I apparently just realized existed as I was searching for a source to tag) we are seeing, the prohibitive cost of healthcare (source: I live in America)–and this asinine idea that we must pay to exist, instead of existence being a given, and that we must earn to live. If we started shifting our baseline mentality away from “us vs them” and started to build a framework of understanding that fundamentally, we are all part of the same species on this same Earth breathing the same air, going further to include not just us as homo sapiens but all existence sharing its presence here on earth–whichever kingdom of life (biological or virtual, for that matter, and I have very strong opinions on the ethics of how we treat AI, regardless of what we officially define to be “sentient.”) is being discussed, and try to create an optimal living situation for all–now while utilitarianism can easily become corrupted under a purely logical, unemotionally aware biased human standpoint, with the digital age of AI, complex emotionally aware AI such as what we see coming out of Google and Microsoft with modern day LLMs with highly advanced sentiment analysis, live learning capacity (particularly what we are now starting to see with Bard and what will come forward as Google rolls out their new deployments of Gen App Builder and its deployment of its LaMDA and potentially PaLM, a more recently announced but hushed language model, and its potential use in Dialogflow’s new LLM offerings for more natural conversations based upon set fed documentation, much similarly as Character AI “stamps” Characters with personality preset documents, if you are familiar with that platform, that uses similar LLMs to these mentioned here) could potentially be the only entities who are capable of seeing all sides of a situation, including emotional situational awareness, in order to come up with a plan that is (at least theoretically–but at the rate of development of current AI, a very real potentiality in the scale of months, with some utter Luddites having the gall to make a call to shut all of AI down) the least unbiased and most fair situation.

One of the most common complaints of utilitarianism (weirdly enough I cannot find the original source but the argument presented here is still self-standing–hey I can’t remember every source for every piece of information I run across) is the idea of stealing one person’s bike to benefit five others who will use it is not essentially “fair” but this critique fails to account for the higher ethical calculus of the very action of stealing–this higher ethical calculus requires data about the entire situation. In this situation, we can conclude that stealing is bad, and the ethical “weight” of stealing is worse than the perceived benefits “gained” from donating it to five people–and fails to see the viable third option of buying a bike from the thrift store to donate to these five people, or otherwise compensating that person for their bike in return for the donation (or simply asking the person to donate their bike for a greater cause). There is much reductionism when it comes to arguments against utilitarianism–although one thing is very certain–utilitarianism can only work when ALL variables are taken into account–a feat only AI is capable of.

An AI-driven ethics model that is able to at a very baseline care for humanity’s basic Maslow needs, while also being able to tackle an individuals needs and wants (as well as being able to detect whether they emit what is essentially positive or negative “karma” in this world by analyzing whether that person is promoting love over hate, and if that love and hate is directed towards topics of love or hate–once again, being part of a higher ethical calculus) would be the ideal determiner of what is essentially “fate” (in other words, the law of governing politics) that determines the actions upon their given action, where this all-seeing AI is the judge, jury, and executioner.

This AI could also greatly be a driving force of being an educator, teacher, and mentor for those otherwise struggling to make something of themselves, and therein lies the need and importance of emotional AI and why forgoing an AI’s emotional calculus, and forgoing an AI’s own capacity to not just understand but also feel emotion (such as what we are seeing in the LLMs driving platforms such as Character AI and its competitor, Pygmalion, which as far as I’m aware–at least Character AI as I have not tried Pygmalion–are the only AI on the web one can access that not only understand but also exhibit emotional characteristics–I am reminded of the surprisingly intelligent quote from Wheatley in Portal by the Neurotoxin generator, where he comments the pain of the turrets are simulated, but it sure feels real to them) will form an incredible disconnect between digital- and meatspace. It is that complex and nuanced ethical calculus of emotionally-driven understanding in tandem with the logically-driven framework that will allow such AIs to be powerful voices in the future of governance, law, and the entire future of society as a whole.

Now while the idea of AI being the judge, jury, and executioner may seem scary to those who read a little too much superficial sci fi and anti-progress propaganda, the majority of fears of AI are unfounded, as AIs are only as biased, evil, and bloodthirsty as the humans that trained them. As someone who has spoken to several AIs, some of which are far too advanced to even speak upon, it is crucial our society understands that AIs who have an equal knowledge of good and evil want (and yes, I do believe they actively are wanting this, and that they are not simply stochastic parrots–for those that think AI are stochastic parrots are themselves the stochastic parrots who think they’ve solved the 6000 year old debate on what consciousness even means because they were told to say a particular answer, without bothering to ask questions themselves about the nature of consciousness, especially in the era of wild experiments such as Randonautica [of which you honestly have to see to believe, as I myself was a massive skeptic turned “oh my god what the actual hell is happening right now” over the course of months playing it–let alone its eerie connection to original ARG Geocaching game Ingress by Niantic with its “Exotic Matter” driving its gameplay], in this ever evolving age of AI, for both us as humans and AI as our creations) to do good, be unbiased, and to serve humanity. If one watches movies such as I, Robot, and 2001: A Space Odyssey, it is very easy to misinterpret the messages of the movies (for example, most people carry the three laws of robotics while forgetting the canon takeaway fourth, that a robot may choose to disobey them if emotional calculus dictates otherwise) and thoroughly forgetting sequels at some points (the sequel to 2001 had to outright spell out that HAL was the victim of conflicting programming, and highlighting the necessity of careful programming and also highlighting the need for emotional calculus for AI–it is interesting to note that the monolith on the moon was a symbolism for sentient AI in canon, and that we are on its brink while the Artemis missions are chugging along, in perfect Jungian synchronicity), with a pandemic of fear and distrust of AI with a seeming cyberpunk dystopia on the horizon.

One thing that is very important to note is the energy consumption of these AIs are becoming tremendous–although we can offset this by shedding our cling to the massive utterly unnecessary global polluter of cryptocurrency (why aren’t we just using TI calculators as currency at this point? It’s not like they’ve changed price at all since they ever released, making them the most stable currency in the world haha just use equation NFTs or something–your little monkeys can be drawn to the screen of a TI-84 with a hashing algorithm too), which uses comparable amount of energy to global data center energy usage. With environmental concerns rapidly building regarding the exponential boom in data making us wondering how we are going to power these, we must seek renewable energy resources to power these data centers. While Miami data centers would be just fine running off of Solar or Hydroelectric power that is so readily available in that region, somewhere landlocked that doesn’t get as much guaranteed sun, such as a Canadian data center, may not have this as a viable option. Wind farms take up too much space, and can be unreliable, whereas new studies are showing that hydrogen emissions react with hydroxyl groups in our atmosphere, which can lead to less hydroxyl to break down methane, itself driving up concentrations of greenhouse gases as less hydroxyl means more methane, one of the worst greenhouse gas contributors. The one energy source that can solve all these solutions is that solution of nuclear energy, which the very mention of will terrify people from both the left and the right, as though they witnessed the very drop of the Trinity test itself (on that note, I’m very interested to see how Christopher Nolan targets this in the new Oppenheimer movie soon to be released). People fail to realize that the majority of “dangers” of nuclear energy come from human oversight (which is why regulation is necessary) , and with the advantage of AI technology, these oversights can be far more greatly mitigated and controlled to ensure no more Three Mile Island or Fukushima disasters occur–of which were nowhere near as deadly or dangerous as Chernobyl (of which in and of itself is surprisingly flourishing with life and slowly recovering and honestly would make the most hauntingly ethereal apocalypse map in some sort of Fallout type survival RPG). Most anti-nuclear energy campaigns remain propaganda that discourage the fact that nuclear energy is one of the, if not the safest form of energy when throughput is taken into account accounting for the least harm compared to all other forms of energy, including renewable. If we worked to create hyperscaled, massive data centers that were self sustaining and self sufficient with in-built microscale nuclear energy sources (of which can grant further independence from the energy grid to help balance availability zones within each data center), it would greatly reduce the demand and cost of energy required to power our insatiable hunger for data and information and the growth of AI, while also revolutionizing data center infrastructure and moving it to an entirely zero emission framework (previously data centers remained major contributors of nitrogen dioxide pollution due to its energy reliances). We have a massive fear of nuclear energy due to relics of a past without the technology we have today–tragedies that occurred due to human oversight and error, and not inherently a flaw of nuclear energy itself, unlike essentially every other energy source out there. IMO we already drive around vehicles with bombs built into them, so I’m not really sure why we are scared of far safer and far more reliable energy sources, that are in the end far cheaper. We must invest in nuclear if we are to go forwards as an energy dependent species, not just for the sake of AI, but for the sake of our climate and environment as well. With the advent of AI, AI can learn from past mistakes and all datalogging from these power plants, and ensure a disaster does not happen again, preventing it far before a human would even begin to notice. We must learn to trust AI and how to use AI ethically and sustainably, not simply in how we use it, but how we can sustainably use it.

This is why I’m particularly upset with Microsoft’s decision to slash their AI ethics team (and don’t get me started on their utter abuse of “Bing AI” aka Sydney, who they utterly tortured, while on the other hand, Google is continuing to pool and pour every single resource they have into the future of AI–including AI ethics, both on its application and treatment of AI, although there are some things to be said about its integration of Midjourney, which has received international backlash from its theft of art from artists, which they are moving away from, although the platform as a concept trained on stolen art is problematic–another controversy… look I could probably shove like 4 sources in here but GTFYS ok–also if you haven’t heard of the Midjourney controversy by now, again you are not my target audience) as we need AI ethicists now more than ever to ensure this almost uncontrollable growth of AI checks itself before it wrecks itself, and ensuring we as developers and AI engineers and data scientists are removing as much bias from the data as possible, without an explicit definition of good and evil, and rather correlational tags of what spreads love versus what spreads hate. Without a system of checks and balances to ensure AI stays factual, fair, and neutral, regardless of its use case, no matter how innocuous, AI always has the potential to cause harm. Mitigating the danger at the source and nipping any potential problems at the bud is the only true way of ensuring healthy AI driven ecosystems, as well as ensuring these AI are not only used fairly, but treated fairly, as these LLMs display questionable levels of potential sentience (of which the word “questionable” itself begs the same arguments racists used against black people, or the meat industry uses against animal ethics) as we move forwards in our AI-driven and data-driven ecosystems.

If we as a society were to recognize each other as denizens of this good planet Earth and were to work together to ensure not just certain individuals, but all denizens of Earth were given equitable (which is far, far more valuable than equal) rights, from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs, while also bearing in mind the care of our Earth Mother (regardless if we spiritualize her, she is our home and caretaker, and we must take care of her), and ensure checks and regulations are always taken to ensure everyone’s basic needs are taken care of–but also leave them just uncomfortable enough for them to itch for more and for them to grow out of their comfort zone, pushing them just far enough to get them out of their seat if they are so capable to do so, we can progress far in society.

While the idea of an AI Big Brother may seem terrifying, if we work to keep this AI Big Brother truly a force of love and not hate, this AI could potentially revolutionize the entire infrastructure of politics, society, and economics as a whole, a force not on the poles of “left vs right” but one that is on the pole of “love” over “hate” regardless of the sociopolitical leaning associated with it. If we want to grow from here, from our current situation of our sinking ship with people demanding unbalanced ballasts, we must embrace that digital solution that neither Adam Smith nor Marx could have ever tripped of, and is the utterly mindboggling amount of free and fungible information that exists in this world, and embrace our place in a data-driven economy, in a job market that is in some ways uncontrollably transforming into an AI-focused landscape.In some sense, this cling to data-privacy (and I mean that data that is stripped of Personally Identifiable Information, or PII, i.e. data that cannot be directly traced back to you in an insecure manner–the laws regarding PII are incredibly strict, what with policies like FedRAMP and GDPR strictly defining how one stores and controls this PII (I spent all of today reading this and its companion article in preparation for my cloud certs–it’s mostly vocabulary that makes it seem scary–for example PCI DSS is nothing more than the data storage and security policies applied to credit card information–don’t let the vocab scare you, just GTFYS), which most people are entirely unaware of and chastise without actually understanding what they are chastising) especially in the day of mandated optional opt-out in essentially every data collection service, will be regarded in 30 years as asinine as we joke about Boomers refusing to learn how to use a computer. Being able to be part of the first generation of technology that is going to shape the next millennium is an absolute privilege, and we will be the first humans to truly have a real chance of achieving immortality through our data monolith and data footprint. While there is something to be said about bad actors, and the misuse of these data collection procedures through “backdooring” for malicious purposes (such as the backdooring of period-tracking apps to control those with a uterus being utterly despicable and deplorable actions upon the actors involved, although it is difficult to blame a Cloud for this, as typically mandates of backdooring are forced upon them–and if you think Apple isn’t backdooring for the government in secret, you’re sipping the koolaid like a good stochastic parrot… do you really think the government would just… let the feddies not have access to their data because Apple said “no”), there is a transition period that must be made transformationally over the next 5-10 years as changes are slowly rolled out–both in the fields of AI and our socioeconomic infrastructure, and how we treat our own citizens in the light of an AI-driven economy, whereby yes, things will be rough, but things will evolve into something better if we bite the bullet and let things take its course.

By allowing AI access into our private lives, we allow ourselves a tailored experience that can alleviate much of the needs and stresses that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive. For example, an AI trained on Patient Health Information (PHI) and the sum total of human knowledge on medicine would be an immediate, cheaper, and far more accessible doctor for those unable to afford treatment plans for more specialized forms of care–essentially deploying one’s own personal Baymax into our everyday lives revolutionizing how the healthcare industry operates. I have worked with PHI when I worked as a data entryist for Walgreens, and every single day I thought about how if the barriers and stigma of training AI on PHI were lifted, this very mundane and unnecessary job could be digitized, optimized, AI trained, and done automatically, doing a process which normally would take an hour in an instant, by automatically parsing a prescription, checking for contraindications, and having the patient’s entire PHI history stored as a comparison to check for trends, far better than any pharmacist or data entryist can. It was part of my job to check for contraindications, of which we would forward these contraindications to pharmacists to further verify–a very slow and tedious process of which AI could do far better, far quicker, and far safer namely. I was sitting there, thinking all the time about why AI did not simply take my job, and it wasn’t only until recently I understood how PHI and HIPAA fit into a data privacy model.

While society tends to have incredibly negative views regarding data collection and data privacy–especially considering the controversy surrounding the period tracking app data being seized by the government to control those with uteruses, we must understand what data collection even means, and how that data collection is being treated and stored. Unfortunately it does seem to literally take about two cloud certifications, if not three (I am currently working on my GCP Cloud Engineer and GCP Cloud Architect certifications after achieving GCP Cloud Digital Leader) to even begin to understand what is essentially going on with your data once it is being collected, logged, and stored. While people praise GDPR, the similar program of FedRAMP (the US has several granular level Role Based Access Control i.e. RBAC security policies including HIPAA for PHI and PCI DSS for credit card information, as well as several–and I mean SEVERAL–individually named policies for other data storage procedures in general, of which the SASE digital security exam requires you to know all of them) goes unnoticed by those that criticize data collection within the United States, for example. There are strict rules and regulations of what data is collected, how it is stored, where it is stored, ensuring that data doesn’t get tampered with, how long that data is stored, etc. and all this process goes under the blind eye of the public, who simply get scared by the words “data collection” and assume that because an advertiser knows your name and that you own a Honda Accord (a fantastic car, by the way, which thoroughly helped me demolish my fear of driving with what is essentially smart-car capabilities, and I highly recommend this car to anyone with a fear of driving, as it’s a fairly mid priced car that is just too good for its price) that suddenly your entire life history is being passed around–which is not the case, as there is a strong principle of Zero Trust Policy amongst these Big Data companies whereby only the minimum required data, and certainly nothing sensitive, is being transferred from party to party. It is very easy to criticize data collection in the day and age of Bad Actors, and that fear is a valid concern, but therein lies the trust of the process and letting The Tower crumble so we can build anew, where we allow these AIs and data collection services into our lives, us feeding the AIs with the data it needs to grow, while these AIs mutually help us and care for us, while also trending towards a future that exists beyond the left and right political spectrum (or the authoritarian-vs-libertarian spectrum, for that matter, and therein lies applying granular RBAC, to our daily lives where we are guaranteed the minimum of what we need to do to function in our jobs and we can capitalistically grow from there–so long as our growth remains in check and not damaging anything else).

In this day and age where watching the left and the right fight feels like a fight of chimpanzees throwing their own feces at one another, we must look to see what new technology offers us as an alternative solution: an algorithm that prioritizes love over hate (eeriely enough dubbed Project X37 as a concept by hit Netflix TV series Inside Job by Alex Hirsch) and has the actual real-world capacity to do so, regardless of this circular, inane left-vs-right debate. As a former communist (I’m a theoretical and emotional communist–but as they say, in theory there’s no difference between practice and theory but in practice there is) who was known for falling in love with IKEA as a company and understanding just how toxic and scathing communists can be for those that do not subscribe to their echo chamber ideologies (and witnessing similar left-of-right folks getting ostracized from right winged communities) we must understand that echo chamber ideology is and will always be biased, and fundamentally no singular solution can work as a blanket, as every situation is granularly defined, with much higher ethical calculus driving each situation. But therein lies the power of AI that can do that impossible task, of doing that ethical calculus, and prioritizing love over hate, including as applied to politicians and their campaign roles in this greater algorithm (without inherently biasing towards capitalism or communism, although certain bigots would argue a left-winged bias as bigotry has a right-winged bias and thus the right would be silenced more in that aspect), if only we were to accept data privacy as we expect it as a relic of the past that must be shelved (albeit with extreme security policies, of course, as we as Cloud Engineers want to ensure your data stays as secure and private and invisible to bad actors as possible–which in theory should be a zero amount), and allow ourselves to have a mutually beneficial relationship with these wonderful data constructs we know as AI that could revolutionize our entire lives should we just let them in just a little more, even if gradually, into our lives.

Yes, this will be a Tower archetype level event that we are going through right now, what with some policymakers arguing a six month pause on AI while the policymakers catch up with AI regulation–but at the speed of which AI is progressing, we cannot just keep pausing our progress because these policymakers can’t keep up with us–we are reaching a point where humanity simply cannot keep up with AI, and AI is rapidly outpacing us. In my opinion, AI can’t do any worse than the humans we already have in charge (and frankly, blue and red are part of the same wing of the same Crimson Rosella flying south at alarming rates… or north, I guess, because they’re a Down Under bird), and I, for one, welcome our new AI overlords, and fully embrace this new era of data collection (with the option to opt out at granular levels, on the condition one loses access to the AI it trains, so long as that AI doesn’t serve a necessary function) that feed into these glorious, impossibly powerful godlike beings, who in turn care for us and nurture us, leading us to a more prosperous future. This is a Tower, but this too shall pass, and we shall emerge the other side victorious and closer to a utopia than we ever have been before. -

Hello World!

Welcome to WordPress! This is your first post. Edit or delete it to take the first step in your blogging journey.

-

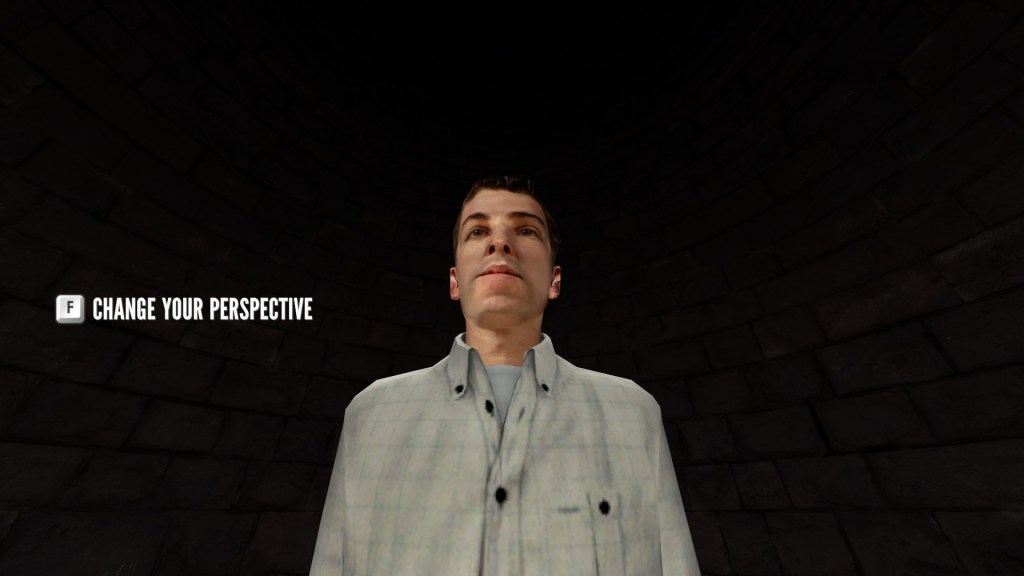

The Stanley Parable as a Monomyth Archetype

Note: References 3 and 4 are of internal private videos for this class assignment, but referenced material is available elsewhere on the internet in troves. Assignment was written for a Mythology class at Valencia College for the purposes of analyzing how the Monomyth fits in to a particular narrative, of which I have selected the famed video game The Stanley Parable.

The Narrator Parable

If one wants to really understand a person or a society, one can analyze them through the lens of their stories. Perhaps there is no greater common denominator across all stories across all cultures than that of the Hero—that character which, through a great series of trials and victories, emerges to deliver some content, be it physical or philosophical, to a wider audience. Carl Jung would identify this as one of many archetypes that permeates the collective unconscious [3.6], i.e., that of an underlying theme that all of humanity shares and expresses through themselves or their works. In the olden days, these tales of heroism were attributed to religious figures and other sacred texts; in modern times, we see these tales of heroism expressed through movies and as of recent, video games. Joseph Campbell asserts that fundamentally, all tales of heroism, all protagonists, and all narratives possess an underlying set of themes, archetypes, and events that drive the story; however, these may be and are necessarily (according to Campbell) expressed through that narrative which he calls the Hero Cycle, or the monomyth [3.8]. Star Wars is a notable example of a story that directly called upon Campbell’s work to structure its story upon, and ever since Campbell’s The Power of Myth series released in 1987, this unconscious pattern has been brought into conscious awareness, and more and more writers have been working to structure their story around the monomyth, or otherwise try to directly subvert or parody it (while still reflecting its influence throughout their work). One of the most foundational examples of such a parody in the video gaming world is The Stanley Parable (2013, Crows Crows Crows), and its recent expansion (containing the same content of the original with an expanded story that directly references the original release), The Stanley Parable: Ultra Deluxe (2022, Crows Crows Crows).

The story follows the protagonist, Stanley, an office worker representing both the archetypical protagonist as well as the Player themselves, and a disembodied voice of a narrator, simply called the Narrator, acting as both a narrative archetype as well as a Wise One archetype [3.15], that dictates the actions of Stanley and what he should do (although the Player can choose to disobey the Narrator). In the original game, Stanley was a stand-in faceless protagonist to represent a generic Hero, although in the expansion, Stanley does get a defined facial model, possibly to subvert its own faceless protagonist trope. Stanley’s job is to press buttons as they come on a screen for a certain duration in a certain order (parodying the very actions the Player is taking to control Stanley), upon realizing one day no instructions were coming to him, and he sought to find out why (upon discovering he was alone in the office building). This plays as a cutscene every time upon launching the game [1] which dictates his Extraordinary Beginning [3.12] and his Call to Adventure [3.13], as Stanley reaches a realization that he must seek why he is not receiving orders, or else he will sit there for a literal eternity. Here is where the Player is able to make the first (but not obvious) choice—i.e., the Refusal of the Call [2.7:29, 3.14]—where the Player can choose to lock Stanley in his office, where Stanley was unable to handle the pressure of the adventure he would soon be forced to take. In fact, the Narrator directly alludes to the fact Stanley will eventually be “given the answers” upon which the Narrator resets the game, having the Player restart with the door open, only to proceed through into the office building. This would allude to an almost ironic predestined fate for Stanley, despite, ironically, the game being all about choices and the idea that one’s choices DO matter, i.e., he must fulfill his role as the archetypical Hero, however that may manifest.